The Prevention and Management of Peri-implantitis pt.2

Video highlights

- Key factors for treatment selection

- Guidelines for resective treatment

- Guidelines for regenerative treatment

- Guidelines for removal of implant

Dr. Michael Danesh-Meyer continues his lecture with the topic of peri-implantitis. When treating peri-implantitis there are mainly three options:

- Resective options

- Regenerative options

- Removal options

Looking at them in more detail, Dr. Danesh-Meyer shares that the main questions usually are: I have a peri-implantitis problem around an implant – which of these options do I chose and how do I decide?

To be able to answer these questions, he invites us to have a closer look at the cause and the severity of the problem. They would need to be assessed so a surgical management plan can be developed. What about the severity of the defect, the consistency, or the quality of the soft tissue around the actual implant or implants.? What access for treatment is possible? How can maintenance be ensured? Is the existing prothesis appropriate or does it contribute to the problem? If yes, how? Sometimes a replace of the prosthesis is part of the management strategy, so the plaque accumulation is reduced, and the cleaning becomes easier. Another question is the strategic importance of the implant. If the prognosis of the implant is extremely poor, is it possible to remove the implant, if the other options are less likely to be successful? This also depends on the position of the implant. If the implant is part of a multi-implant rehabilitation, this can be a problem, especially if a key implant is concerned so the entire prosthesis is impacted. Dr. Danesh-Meyer summarizes that the position of the implant, the patient’s preference, additional costs, and adverse effects should be looked at and assessed on an individual basis. Also, the age of the patient is a factor that influences how the situation is handled. The patient themselves is part of the decision process regarding if they present other risk factors that are associated with the peri-implant disease and that need to be managed as part of the process, too. This could be smoking, poor oral hygiene, other systemic conditions that can be predisposing factors for infections, e.g., diabetes. Do they have a history of periodontal disease? When inspecting the actual implant, are there iatrogenic causes, is there excess cement? This was a common issue from the early 2000’s to 2010, when cement-retained restorations were very common. With this kind of restoration, a common iatrogenic cause was excess cement being trapped beneath the soft tissue, causing massive inflammation, and leading to massive bone loss – if not addressed early. As there is a movement from cement-retained restorations towards screw-retained restorations, this issue has become less and less.

Another influence are implant surface properties, according to Dr. Danesh-Meyer. Looking at machined versus enhanced surfaces, this could influence the undertaking of a resective approach. With machined titanium implant surfaces, biofilm formation will be less of a concern as opposed to a moderately roughened implant surface. The categorization of peri-implantitis is difficult, but Dr. Danesh-Meyer tries to help us with categorizing it in three main areas: early, moderate, and severe presentation. As every patient is different, one cannot generalize, but some guidelines can help as to what the likely treatment will be for an early presentation. This is a more straightforward treatment, and there may be some open debridement, and surface detoxification. If there is a more significant bone defect or sulcular intrabony defect around the implant, not only debridement and cleaning of the implant surface needs to be considered, but also possibly regeneration, if the osseous lesions lend itself to it. The other extreme we have cases with significant amounts of bone loss and perhaps an unfavorable pattern of bone loss, the type, or the way the bone loss occurs, where sometimes the only remaining options is the explantation of the implant. A lot of the decision-making is based on where the implant is positioned. A resection will result in the exposure of the implant abutment and potential exposure of the implant itself. This may not look too good, especially in esthetic zones and places that the patient is going to show. With this the option becomes rather difficult, as the patient does not want to go around with bits of metal showing in their smile line. The position of the implant can influence whether this is a path to follow or not, in cases where the regeneration due to the nature of bone loss is not really feasible or has very low predictability, this is a good option. In non-esthetic zones, the patient may be able to clean much more effectively thanks to the resective treatment. He points out that this is good option and will prolong the life of the implant. It can also help to stabilize the peri-implant tissue health in those cases, according to Dr. Danesh-Meyer. What about cases with a well-defined infrabony defect? Cases with a good soft tissue quality around the implant, maybe in a category where regeneration is an option. Normally, this would involve some form of full-thickness flap, it involves removing a lot of granulation tissue, it involves cleaning of the implant surface in some way and using GBR techniques to try and regenerate some of the damage caused by the inflammatory condition. When assessing the case, it is very important to look at the severity and the pattern of the bone loss. Cases with class I to class IIa show a confined bone loss. These cases, even including class IIb, with still significant amounts of bony walls present, provide the osteogenic potential for regeneration into the defect, and may lend themselves quite well to regenerative therapy. Moving on to class III, class IV, and class V defects, we can see the amount and pattern of bone loss is now very different. What kind of osteogenic potential, regenerating bone to the collar of the implant, is possible with a class V scenario? The only place, where bone can likely come from it way down low, Dr. Danesh-Meyer emphasizes. And the chance of this being successful, even with all available grafting options, is extremely low. In a class V situation, we are looking at some form of resective management or possibly even explantation. Closely following is class IV, and class III is challenging, too. He reminds us to evaluate in a case-by-case manner, and this overview should provide the defects we could be dealing with, and which ones can be favorable for GBR. Favorable are class I to class II, including class IIa and class IIb. An ideal situation has a good quality and quantity of soft tissue, and keratinized tissue in the respective area. If this is not present, there may also be a need for some form of soft tissue augmentation as part of the GBR protocol or prior to the GBR, to ensure a higher degree of success of the GBR treatment. Many cases the quality of the soft tissue around the implants is poor, so this creates a more complex management strategy as we need to look at using soft tissue augmentation in conjunction with GBR. Other additional factors can make the problem even worse; he emphasizes. The patient may have a poor systemic health, they may be a smoker and may have other issues. Asking the body of such a patient to recover following a GBR procedure with all other unfavorable factors in the mix, is not going to be a success. So maybe the removal is the most appropriate management option in those cases. Alternative options or possibly a retreatment can be considered if the present factors can be modified to turn the patient into a more ideal patient – from an implant retreatment standpoint. Looking at the literature in relation to regenerative therapy around peri-implantitis cases, we can see that actually evidence is emerging that this can be helpful in the right case. There is evidence of recovery of bone levels, there are improvements in peri-implant tissue health if these things are done properly, Dr. Danesh-Meyer highlights. As there are many factors involved in determining success in terms of outcomes, there is a bit of variability in the periodontal research in the literature.

One key point critical for a regeneration to be successful, and which has been a longtime struggle regarding peri-implantitis management, the ability to clean the implant surface and remove the complete bacterial biofilm so we can hope to allow the bone to re-osseointegrate onto the implant. Over the years there have been many different options suggested how to clean the implant surface, like titanium brushes, different types of scalers, chemical treatments and in more recent years, air-powder prophylaxis, lasers, and electro-chemical cleaning. In his lecture, Dr. Danesh-Meyer is focusing on the last three mentioned options as they are becoming probably the mainstay for management of the implant surface. Removing the biofilm from a moderately roughened implant surface is a significant challenge. The other point increasing the difficulty of the management is the nature of the bone loss. If implant show intrabony components, getting the instrumentation into the area where the implant surface is covered with a biofilm is very difficult from an access standpoint. Air-powder prophylaxis has been around for some time, but there are limitations. Sometimes it is difficult to get the instrumentation to actually engage onto the surface of the implant due to anatomical limitations. There is also the risk that it is unknown how much powder is remaining on the implant surface or within the wound even when flushed with sterile saline. As a flap need to be raised, the risk of an air embolism is present as well. He reminds us to be careful when using these instruments. The situation is messy with water and air powder flying around in an open wound, it is not ideal. Studies suggest that in terms of creating a sterile or clean implant surface it is not always predictable and there is evidence of culterful bacteria being present after air-powder prophylaxis, creating an issue. What about lasers? There are several lasers that have been proposed, and it is known that lasers can sterilize and will kill bacteria very effectively. Dr. Danesh-Meyer shares his experience in using an Er;Cr;YSGG laser and studies show that the use of this tool when used on moderately roughened implant surface, a cleaning can be providing which is comparable to the implant at the time of unpacking. This is encouraging as not only physically we can see the biofilm being removed, but also bacteriology shows a reduction in the amount of viable fluor remaining after laser application. A flexible radial tip on the laser is a benefit in terms of gaining access to deep, narrow intrabony defects. It is also known that the laser will not alter the implant surface, but some lasers may generate heat. He highlights that we must look at the type of laser carefully and how it is going to interact. If we can be confident that the implant surface is clean and free of bacteria, we can be more confident, that a regenerative procedure will have a more successful outcome. He shows a case illustrating that had poor soft tissue quality and quantity which contributed to the peri-implant breakdown. To treat the shown case, not only a GBR of the intrabony defect was done, with a cover with a resorbable collagen membrane, also a connective tissue graft to ensure and increase the thickness of the soft tissue was done. Among the tools available today is GalvoSurge, a tool for a novel way of implant cleaning, using a non-toxic, electrolytic solution consisting of water, lactic acid and based on sodium liquid. An electrode is placed on the implant surface and then the implant surface is flushed, and the electrode is loaded with a low voltage, creating hydrogen bubbles on the implant surface beneath the actual biofilm. They will remove the biofilm from the surface outwards, which is a unique process as opposed to other techniques essentially trying to approach it from the outside of the biofilm towards the implant surface, like a reverse process. Dr. Danesh-Meyer shares that he is using it in the clinic for some years now and can confirm the reliability of the device. It will not remove mineralized deposits, so they would still need to be removed separately. The advantage of this system is that the biofilm even in narrow intrabony defects can be removed and there is no damage, change or alterations of the characteristics of the implant surfaces. The limitation of this tool is, that the prosthesis needs to be removed to engage the electrode with the implant. If this can’t be done, it either needs to be cut off or an alternative option need to be explored. Based on his experience, he can confirm to see some great improvements irrespective of the type of the implant surface. Using an SEM, we can see that a clean surface will be provided, comparable to the sterile implant surface from the packet. The use of such tools is enhancing the ability to promote re-osseointegration. He shares a case, demonstrating the use of the tool in the clinical setting. After 9 (nine) years of function, the patient developed a pocket, there is bleeding on probing, light suppuration and radiographically bone loss is visible. A full thickness flap was raised, and a narrow intrabony defect could be identified. Mineralized deposit was removed as well as granulation tissue, GalvoSurge was used to remove the biofilm, and the soft tissue was closed with a 4.0 monofilament Teflon suture. A follow-up images shows the situation 14 days after the surgery with very little inflammation present and a good healing process. He continues with a 2-year follow-up image, presenting stable bone margins, stable peri-implant tissue health and an overall good result, giving the implant several more years of function.

A critical element of the treatment is not only doing a regenerative procedure, but also ensuring that the patient follows with maintenance and upkeep and supportive therapy post peri-implantitis treatment is important. This is substantiated by a study showing that when supportive therapy is provided over a 5 -year period, success is predominant. But, in some cases, despite the best efforts and desires, we are unable to safe the implant. If the bone loss is severe and the bony defect does not lend itself from a biological standpoint to regeneration, the only option remaining is the removal of the implant. Dr. Danesh-Meyer explains that his preference is to keep this procedure as minimal invasive as possible and uses a reverse-torquing type of removal. In cases with a bone loss over 50%, this has proven itself as a good and predictable solution to him. There may be situations when a trephine needs to be used, however these drills created other problems. If an implant is to close to an adjacent tooth, a trephine cannot be used. Also, the osseous defect will be much bigger when using a trephine as opposed to using the reverse-torquing technique and recovery will be faster and the collateral damage can be reduced.

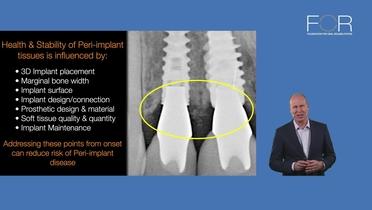

Summarizing his lecture, he points out that the management of peri-implantitis is complex, and there a lot of issues to consider. Prevention through careful treatment planning and execution of the treatment from the beginning is paramount of avoiding the problem in the first place. Implant and prosthetic design, and materials used, especially those of the prosthesis, can influence the peri-implant tissue health. It is important to identify the causative factors in the diagnosis of peri-implantitis as they may be multifactorial and each one needs to be addressed to achieve success. The pattern and the severity of bone loss around a peri-implantitis case will certainly determine what type of treatment modality we chose to apply and the likely success of it as well as the understanding of the limitations of those procedures is also important. Professional maintenance is key and the therapy of peri-implantitis followed by regular supportive care can result in a very happy patient.

It appears the GalvoSurge is not available in the US.